Phil Solomon, Leading Experimental Filmmaker, Is Dead at 65

Phil Solomon, who used repurposed footage, manipulated images and striking soundtracks to make evocative experimental films that were widely admired by hard-core cinephiles, died on April 20 near Boulder, Colo. He was 65.

Mr. Solomon, an emeritus professor of cinema studies at the University of Colorado at Boulder, took up the experimental-film mantle in an era when the lure of feature filmmaking was irresistible to most of the creative young minds in cinema. His films, usually relatively short, did not have stars or plots in any conventional sense; he was after something more cerebral.

New York Times

Movie film, from the suitcase-sized film reels they used to show in the multiplex projection room all the way down to the home movies your grandfather used to shoot, is made from two materials: a polyester or plastic base, durable and relatively scratch-proof, and a layer of gelatin1, rendered from the bones of dead animals, in which are suspended microscopic particles of metallic silver and tiny splotches of various colored dyes.

- 1 Why gelatin? After all these decades there’s still no synthetic substitute capable of doing what gelatin does: when wet, it swells to many times its original volume and its spaghetti-like protein molecules relax and straighten, which allows particles of silver nitrate — the active ingredient in photography — to flow into the gaps, where they’re trapped and securely suspended as the gelatin dries and the proteins once again curl, shrink, and wrap tightly around each other.

The ideal, for all of photography’s century-plus of history — the unreachable end goal of billions of dollars of research and development on the part of giant corporations like Kodak and Fuji — has been for the film medium to be a perfectly transparent window through which the story, the action, the images can be seen as clearly as possible.

Phil Solomon’s films wanted nothing to do with this kind of clarity. They bear the scars of various kinds of mistreatment of the fragile, organic, gelatinous layer of the film strip, and as a result the images are shattered like glass, or bubble like boiling liquid on a hot surface, or are shot through with vermiform lines burrowed by grasping tendrils of mold that have grown in water-damaged film reels.

Their soundtracks2 are built up from layers of ambient sounds, suggestive sound effects, muffled lullabies, half-audible orchestral themes, in a bed of rain or wind or the dusty crackle of an empty record groove, an auditory texture that’s every bit as rich as the intricately decayed images.

- 2 You’re lucky they have soundtracks, to say nothing of human faces and figures, as the experimental-film world is full both of silent works and of abstractions with no recognizable figurative images, films made of nothing but flickering colors or, in one case, Stan Brakhage’s majestic Passage Through: a Ritual, nearly forty-five minutes of pure, blank blackness punctuated by just the occasional half-second flash of imagery.

Remains to be Seen

Phil Solomon | 1989/1994 | 17.5 minutes | COLOR | SOUND

Rental Format(s): 16mm film / Super 8mm, 24 fps“In the melancholic Remains to be Seen, dedicated to the memory of Solomon’s mother, the scratchy rhythm of a respirator intones menace. The film, optically crisscrossed with tiny eggshell cracks, often seems on the verge of shattering. The passage from life into death is chartered by fugitive images: pans of an operating room, an old home movie of a picnic, a bicyclist in vague outline against burnt orange and blue … Solomon measures emotions with images that seem stolen from a family album of collective memory.” – Manohla Dargis, The Village Voice

Description of Remains to be Seen from the catalog of the San Francisco–based experimental film distributor Canyon Cinema

It would be another ten years before Phil was diagnosed with the lung condition that would eventually kill him, but his tribute to his mother was full of images and sounds that seem now to have been premonitions: scenes of operating-table action, scenes of lonely solitary convalescence, scenes of seemingly half-remembered family outings, all soundtracked by labored, respirator-assisted breathing, the beeping of a pulse monitor, and claustrophobic liquid sounds drowning out barely perceptible whispers.

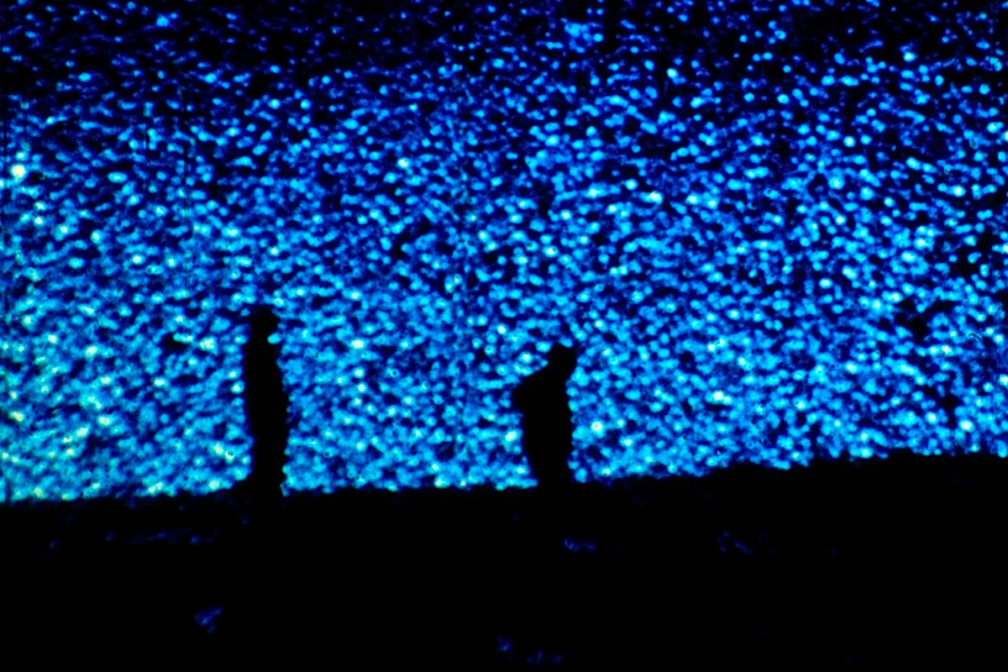

The film ends with an extended shot of a pair of figures in silhouette, one standing tall and healthy, the other stooped and elderly, against a sky that’s the purest blue you can imagine. The sound of the lapping of the surf places you on a beach, and the elder figure slowly, tentatively, begins to walk away, towards the right edge of the frame. Into the sea. As she departs, a pulsating orange flare begins to lap at the left edge of the frame, behind both figures. It’s an artifact of light unevenly striking the edge of a spool of improperly handled Super-8 home movie film, a “mistake” afflicting the original source footage, and this pulse of light, this solar flare, ebbs and flows, but comes back bigger and redder each time it returns. Just when the elder figure is about to leave the frame, the flare stretches across the width of the screen, swallowing them both. Cut to black.

When I was his student, Remains to be Seen was the film we all wished we could have made, and the kind of film we hoped against hope that we someday would make. Not just for the impossible, impossibly beautiful texture of it, the never-revealed chemical treatment that turned the image’s surface into crystals or pebbles or shards of splintered glass. And not just for the sheer cinematic luck of having found such suggestive footage to use as a source for his manipulations. We revered Remains to be Seen because, as myopic as we might have been in our maniacal focus on craft and technique, we recognized in this film the possibility that a so-called “experimental” film — this marginal art form that is the haunted shadow of the Hollywood film, made from its cast-offs, its decaying corpses, its industrial byproducts, its literal garbage — could be a work as great as any poem, any painting, any symphony.

A week after Phil’s death I went back to Boulder for his memorial screening in the gleaming new Cinema Arts building that now stands on the University of Colorado campus, on the footprint of the run-down, disused museum-department warehouse from which the film program of my years borrowed its cramped and musty rooms.

Phil had dictated the program for this final screening in the text of his will, right down to the sequencing of the films. The first, of course, would have to be Remains to be Seen — he was never one to pass up the opportunity to add a new layer of resonance to an old title. He knew that these films would be his remains, and that a filmstrip isn’t a film until it’s seen.

The Snowman

Phil Solomon | 1995 | 8 minutes | COLOR | SOUND

Rental Format(s): 16mm film

A meditation on memory, burial and decay — a belated kaddish for my father.The Snow Man

by Wallace StevensOne must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitterOf the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare placeFor the listener, who listens in the snow,

Canyon Cinema catalog entry, including the full text of The Snow Man by Wallace Stevens

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

A few years after Remains to be Seen, Phil’s father would be dead, too, and The Snowman is about this loss, and so many others. In it a child, bundled up in a one-piece snow suit, is repeatedly seen pretending to shovel snow, in a gesture that evokes the ceremonial first shoveling of a Jewish burial. Its soundtrack contains, beneath the sound of the whipping winter wind, a field recording taken from Phil’s father’s own memorial service.

A kaddish is a Jewish mourning prayer — and all of Phil’s works were, in their way, mourning prayers. It seems significant that in Jewish liturgical tradition a kaddish is never said in solitude, but always requires a congregation. So, too, does film, at least this kind of film. These images don’t translate well to video, still less a solitary laptop screen. Their visual texture depends on the inky shadows and the silver glimmers of light projected through a film strip, and their emotional resonance requires a hushed, darkened room and an audience who, together, wishes them into existence. There’s an element of ritual, of collective belief in the possibility and necessity of this kind of art, so economically marginal and so culturally obscure that it depends for its very existence on a congregation that sustains it by a mutual good will that resembles, at times, religious faith3.

- 3 This kind of film — meaning so-called experimental or avant-garde or artists’ film as a form distinct from “the movies” — is a mourning prayer in other ways, too. Hollywood films are projected digitally now, even in theaters. They’re often watched on TV screens or laptops or even phones, often alone. And they’re almost always, now, photographed digitally as well — there are a few notable holdouts among high-prestige productions, but for the most part film photography is more difficult, more expensive, and reserved as a sort of artisanal luxury option, For the most part, those silver particles, suspended in gelatin, are a thing of the past. While digital films exist in a multitude of exact copies on networked hard drives, film films are sealed in metal canisters and stored in carefully maintained conditions, presided over by archivists, protected against inevitable decay by preservationists, brought out only for ceremonial screenings before being gently cleaned and returned to their vaults.

I never entered this clergy, but I would remain a believer. I took what I learned from Phil — about the Romantic sublime and the austere beauty of high Modernism, about Charles Ives and the process music of the Downtown minimalists, about Transcendentalism and other kinds of transcendence — into my life as a musician, as a photographer, and as a writer, and as someone who believes that art is made from the same stuff as everyday life, and that life is made from art.

Years later — seven or eight years ago now — I got in touch with Phil again through, of all things, Facebook. For a while we worked together on a book, made from transcriptions of his vast collection of recordings of his talks with other filmmakers and artists. In this process we became friends, though I would always also be his student, and he would always also remain my teacher. We would eventually shelve this book — he knew, and said explicitly, that he didn’t have time to do all the things he wanted to do, or to make all of the things he wanted to make, though he didn’t, in the end, know just how little time he had left.

Three years ago Phil formally retired from his university post, both in recognition of the increasing physical demands of his illness and in an effort to make the most of his remaining time. His retirement celebration was joyful, but not only joyful — though he was surrounded by friends, family, and many, many former students, it was a bittersweet occasion, because he wasn’t ready for his teaching career to end. He was an extraordinary artist but he was no less extraordinary a teacher, and he was unmistakably disappointed to have taught his final class.

Among Phil’s late works was a film called Rehearsals for Retirement, a title taken from a song by the folk singer Phil Ochs4. All of us present at his retirement had been carefully taught not to stop at the literal meaning of a word, or a phrase, or a title. I think everyone there knew that his retirement was a rehearsal, and I think we all knew what it was a rehearsal for.

- 4 The song appears on an album also titled Rehearsals for Retirement, whose cover art features a photograph of a mock tombstone bearing Ochs’ name.

Many of his early films were about the loss of his parents, and Rehearsals for Retirement was part of a trilogy about the loss of his best friend. Others were about the loss of youth, of innocence, of memory, of life and light. Later films were about losses on a world-historical scale, from the loss of the idea behind America’s founding to the loss of six million Jews (and so many others) in the Holocaust.

One must have a mind of winter, one must have been cold a long time, to look on this wintry, windswept world and not hear the sounds of misery in this bare place, to see nothing that is not there — to not recall, always, the faces and the voices of the departed, to not see their memories evoked in the world from which they’re now absent. Phil never had a mind of winter — I don’t think he ever beheld the junipers shagged with ice without feeling the suffering of this world. I don’t think he ever beheld “the nothing that is” — I think his art, and his life, was about the everything that is, the things and people and places of this world, upon which his gaze was lovingly fixed until the end.

- 5 Or the blue spruce, the state tree of Colorado, a place where Phil, born in Queens, raised in the New York suburbs, always felt like an exile — not to mention a place that, because of its high elevation and thin, dry air, would always feel like a hostile foreign planet to a man whose lung tissue was cracked by scar tissue created by a condition that he had silently inherited from one of his parents, long departed.